Thirty years ago, an illegal dumping ground at Roosevelt Road and Kostner Avenue caused one hardship after another for residents of Lawndale’s K-Town neighborhood. The lot, called Mount Henry, was piled six stories high with hazardous waste while neighbors struggled with respiratory disease, rat infestations and crime.

In 1996, it was revealed why government agencies turned a blind eye to the dumping ground: the man who orchestrated the dumps was an FBI mole involved in a corruption sting known as Operation Silver Shovel. They allowed the dumping in order to catch politicians being bribed into allowing the dumping. The site wasn’t only home to hazardous waste — it was home to corruption.

In the years after the lot was cleaned up, several plans emerged to redevelop the land and turn the city-owned site, which was a scar upon the community, into a triumph that could usher jobs and wealth into Lawndale. But one after the other, those plans fell through, and nothing materialized — until now.

City officials pledged to revitalize the former Mount Henry dump through an INVEST South/West process with an unprecedented level of community engagement. But the city ultimately chose a redevelopment plan that was not a top contender based on community input.

From a pool of six competing development teams, the city chose Related Midwest and 548 Development’s plan to build an industrial complex housing freight, distribution and cold storage tenants. The plan will also include a community innovation center, a rooftop solar farm and a park. The development promises to generate 700 permanent and temporary jobs and offer workforce training programs and business incubation space.

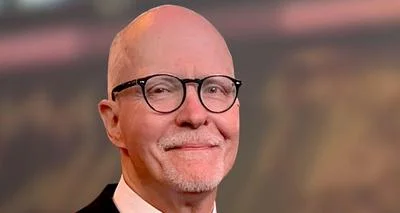

The project “brings to close one of the most nefarious chapters in community disinvestment that Chicago has ever seen,” said Maurice Cox, commissioner of the city’s planning department.

The project has benefits for a neighborhood hungry for investment after decades of neglect. But it was a dark horse that rose from the bottom half of the shortlist.

The six teams of developers vying to build on the vacant Silver Shovel lot presented plans at a series of community meetings in 2021. Feedback from residents who attended the meetings and from a follow-up survey was consolidated into a three-point scoring system that was taken into consideration by city officials as they selected a shortlist of developers and the final project, planning officials said.

“We issued the community-driven [selection process] for the redevelopment, and we intended to raise the bar across the board and prove … it could be designed in a way that actually gives something back to the community, especially through some of the outward facing amenities that we’ll see along Roosevelt avenue,” Cox said.

Evaluations from the city’s own Department of Planning and Development and from residents show the Related Midwest and 548 Development plan wasn’t initially a top contender. On average, residents rated the winning plan third out of the six proposals.

The planning department scored the Related Midwest proposal even lower. The city’s initial evaluation looked at the feasibility of each project, design excellence and the ability of the project to create community wealth. The Related Midwest and 548 Development plan was ranked as fourth of the six plans in that evaluation, records show.

“There should have been more information provided as to why they selected this one that had such a poor rating,” said resident Mamie Gray, who was rooting for a plan by Pritzker Realty and Cubs Charities that would’ve turned the site into a warehouse and a sports and recreation complex for youth. “How did they come out of the ashes? You need to let us know because that wasn’t our choice.”

The final redevelopment plan picked by the city also differs significantly from what was initially proposed to residents at the March community meetings. Related Midwest and 548 changed their architect after the initial evaluations, adding Lamar Johnson Collaborative to the development team.

“We were in the deep end of the pool, and we were all nervous about Commissioner Cox’s [expectations for] design excellence. So at the 25th hour, I called … Lamar Johnson Collaborative … to sprinkle something extra,” AJ Patton, CEO of 548 Development, said at a press conference this week.

A park and public art was also added to the project behind closed doors without an opportunity for residents to offer input on the changes through the city’s process.

When the shortlist of development finalists was announced in March, city officials pledged there would be a second round of public review meetings starting in May for residents to offer input as developers refined their plans. But those meetings never happened.

“It did go into the dark, into a black hole, after the six projects were presented,” Gray said. “There was not much involvement of the community after that. It was behind closed doors, in a smoke-filled room.”

Ald. Michael Scott Jr. (24th) said he did collect feedback from some residents at ward meetings.

Lightfoot said it’s expected that development plans will change amid the selection process as city planners “push the developers on things that we’ve heard from the community that may or may not be in their initial proposal.”

“It’s an iterative process. And the final product, hopefully, is one that incorporates as many aspects of what the community says it wanted,” Lightfoot said.

But some residents said the significant changes were a bait-and-switch, where the plan that was presented wasn’t the same as what was being evaluated behind the scenes.

Remel Terry, vice president for the Westside NAACP and a Lawndale resident, was part of the neighborhood’s INVEST South/West roundtable to guide the initiative’s projects in the area. Terry criticized the lack of transparency in how the final decision on the Silver Shovel project was made and said the late changes to the plan were like “switching up the rules” midway through the process.

“Someone could have been given a leg up. It wasn’t what was presented. So to switch at the end, it’s really concerning,” Terry said.

Promises of community-led development always seemed vague since the planning department hadn’t defined how much community input weighs into final decisions, Terry said.

“We would’ve never thought that someone who scored poorly would be at the top,” Terry said. “We don’t have the criteria in which the decision is being made. All we can do is assume.”

Lightfoot said the choice ultimately came down to feasibility. The 548 and Related Development plan scored slightly higher on financial feasibility than the project ranked highest overall by the planning department’s evaluation, the Westside Works proposal from Matanky Realty and Safeway Construction. But the Westside Works plan was rated a full point higher on the three-point scale for another feasibility metric that took into account land use and environmental strategy.

“Community input is a very valuable part of it,” Lightfoot said. “Obviously, having a great vision that can’t actually come to fruition because there’s not the appropriate financing in place, that does a disservice to the community.”

Feasibility was especially important for this site since previous attempts to revamp the vacant land had fallen though, Scott said. Selecting a more expensive project would do nothing but harm residents who had already suffered extensively due to the lot, he said.

“We’ve had several people who have attempted to do things on this land before,” Scott said. “It has to do with jobs and feasibility and the amount of city subsidies needed in in order for this to work. When you piece all of those things together, this is clearly the project that we know will get done.”

With the site’s legacy, “you had to pick something that was going to get done, and get done in an equitable manner,” said Patton, the developer.

“If they pick a team and it fails, you’re not going to go back to the community and say they picked the wrong horse,” he said. “At the end of the day, all of this falls on the mayor’s desk. It is well within her right to make sure they pick the right one.”

But the selection process and its outcome have left some residents wondering why they were asked to participate if their voices ultimately weren’t a deciding factor.

“It felt like the decision had been made regardless of what I said. It was like the horse had left the barn,” Gray said. “Why ask for community engagement? Why invite us to the Zoom meetings if you’re not going to take our selections seriously?”

Alerts Sign-up

Alerts Sign-up