A federal civil lawsuit against several former detectives who have been accused of misconduct since 2001 is starting to put the media on trial.

Chicago City Wire revealed in a story last week that the reversal of a conviction for Tyrone Hood for the 1993 murder of Marshall Morgan Jr. was the result of a media campaign by a collection of media broadcast and print outlets, including the New Yorker magazine, according to a recent motion filed in federal court.

It was this media pressure, not evidence in the case, that compelled former governor Pat Quinn to commute the sentence of Hood and another offender, Wayne Washington. Hood’s conviction was then vacated by Cook County State’s Attorney Kim Foxx.

Quinn’s decision to release Hood came in the waning moments of his administration after he lost the election to Governor Bruce Rauner. Hood wasn’t the only one let out by Quinn on that day under the most suspicious circumstances. The former governor also commuted the sentence of Howard Morgan, convicted on four counts of attempted murder of four Chicago police officer after Morgan shot some 17 rounds at the officers during a traffic stop, wounding three.

Quinn also commuted the sentence of Willie Johnson, who had been convicted of perjury for lying in a post-conviction proceeding that the two convicted killers were actually innocent of the murders.

Citing a collection of phone calls to Johnson in Texas from an incarcerated top gang member shortly before Johnson recanted, neither then State's Attorney Anita Alvarez nor the judge at the post-conviction hearing believed Johnson’s sudden change of story. Alvarez charged Johnson with perjury and he was sentenced to several years in prison before Quinn suddenly commuted his sentence.

Three highly suspicious commutations, including one for a man convicted of trying to murder four police officers, cried out for intense media scrutiny, yet Quinn’s egregious abuse of his powers generated little if any investigative reporting.

So too has the recent motion by city attorneys in the Hood case pointing a finger at media activism as the driving force in Hood’s release.

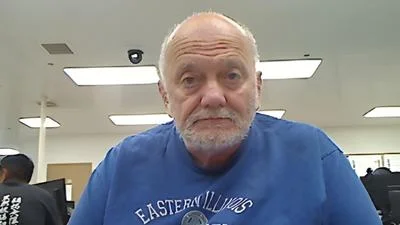

One of the detectives who worked the Hood case was Kenneth Boudreau, who has been targeted since 2001 in a series of Chicago Tribune articles claiming a pattern of misconduct by Boudreau and others who worked with him.

Willing to risk everything, Boudreau and several other former detectives are fighting the Hood lawsuit and several others accusing them of misconduct, including a lawsuit brought by Nevest Coleman and Darrel Fulton for the 1994 rape and murder of Antwinica Bridgeman in Coleman’s basement. Police discovered Bridgeman’s badly decomposed body in the basement with a metal pole forced into her vagina.

There are compelling signs that case, too, may be the product of a media campaign. Since Coleman and Fulton were released amidst a circus of media coverage often citing a “pattern” of coerced confessions by Boudreau and his partners, the same media has gone silent as city attorneys deposed top prosecutors in Foxx’s administration who stated that, despite Coleman’s “exoneration” they still believed the men were guilty of the murder and that the detectives did not coerce a confession from Coleman.

It goes on and on. Was it evidence or media pressure that was key in releasing Anthony Porter for a 1982 double murder, a case that paved the way for a host of other exonerations made by former Governor George Ryan at the same time he himself faced a 21-count indictment for corruption? Was Ryan responding to evidence or, like Pat Quinn, media pressure in using the Porter case to justify the release of four convicted killers from death row, including Madison Hobley for an arson that killed seven, two of whom were children, and injured dozens others?

The city attorneys’ argument that a media campaign is the driving force in a criminal case, not evidence, could explain one phenomenon Chicago’s media machine uses in casting doubt on accused police officers: the decision of cops to listen to their attorneys and plead the Fifth when they are accused of misconduct. A detective, after all, faces great risk testifying in a court of public opinion controlled by malevolent media forces.

In a Chicago City Wire article, former Detective Boudreau described how the errant media stories are cited by the attorneys like those from the law firm Loevy and Loevy representing the so-called exonerated men.

“If you look at all the Loevy & Loevy complaints, they cite these articles in their civil complaints to be used against us," Boudreau said.

Boudreau paints an ominous picture of a breakdown between the crucial checks and balances provided by an independent watchdog media, suggesting the media may not only be unduly influencing elected officials but also the public who will serve on juries. As the stories are repeated over and over while crucial developments undermining them are ignored, are jury pools being spoiled by media activism?

It’s time for an accountability of the Chicago media in the Hood case and others, the kind of accountability the same media machine chronically calls for in the police department.

Because everyone is equal before the law.

Alerts Sign-up

Alerts Sign-up