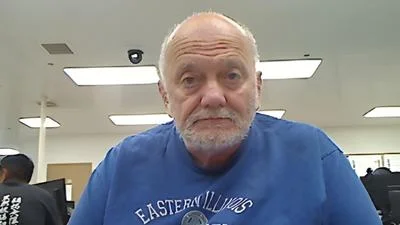

Charles Katzenmeyer Vice President, Institutional Advancement | Field Museum

Charles Katzenmeyer Vice President, Institutional Advancement | Field Museum

In a recent study published in the journal Evolution, researchers have explored the evolutionary changes that occur when birds lose their ability to fly. The study focused on comparing the feathers and bodies of flightless birds with those of their closest flying relatives. This research aims to understand which features change first during the evolution of flightlessness and which traits take longer to evolve.

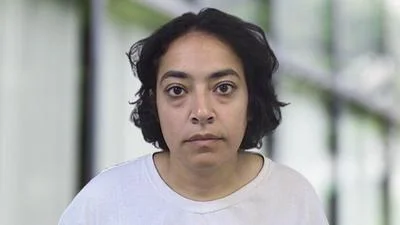

Evan Saitta, a research associate at the Field Museum in Chicago and lead author of the paper, explained, “Going from something that can't fly to flying is quite the engineering challenge, but going from something that can fly to not flying is rather easy.” He noted that flightless birds today evolved from ancestors capable of flight.

Birds typically evolve flightlessness for two main reasons: adapting to predator-free islands or developing semi-aquatic lifestyles. For instance, penguins have adapted to "flying underwater," leading to changes in their feathers and skeletons.

Saitta's interest in this topic was piqued by access to extensive bird collections at the Field Museum. His exploratory study involved measuring various features of feathers from 30 species of flightless birds and their closest flying relatives. He also examined other species to represent more of the bird family tree.

The study found significant differences between species like ostriches, which lost flight long ago, and others like Fuegian steamers, which lost it more recently. “Ostriches have been flightless for so long that their feathers are no longer optimized for being aerodynamic,” Saitta observed.

Surprisingly, it takes a long time for flightless birds to lose feather features optimized for flight. Saitta’s postdoctoral advisor Peter Makovicky pointed out that developmental constraints play a role. Feathers follow a well-defined developmental sequence that's hard to alter quickly.

The research revealed that larger skeletal features change relatively quickly after losing flight ability. “The first things to change when birds lose flight...is the proportion of their wings and their tails,” said Saitta. This is because growing bones requires more energy than growing feathers.

These findings could aid scientists in determining whether fossilized birds or feathered dinosaurs were capable of flight. Saitta stated, “Our paper helps show the order in which birds’ bodies reflect those changes.”

Saitta's work aligns with previous studies showing increased symmetry in a bird’s flight feathers after losing flight capability. He concluded, “We got results that are very consistent with a lot of the previous research.”

Alerts Sign-up

Alerts Sign-up