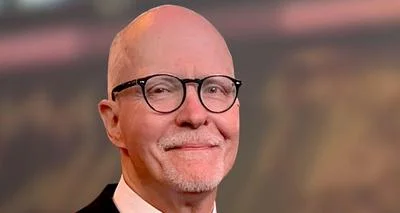

Nick Trutenko | GoFundMe

Nick Trutenko | GoFundMe

A little noticed but enormously consequential acquittal verdict in a criminal case against two former Cook County Assistant State’s Attorneys (ASAs) might have spared prosecutors everywhere from being targeted with trumped-up charges based on unsubstantiated allegations of misconduct. The February 19 acquittal of Nick Trutenko and Andrew Horvat by Judge Daniel Shanes, Chief of the Criminal Division in Lake County, also stands as a preemptive strike against plaintiff attorneys dreaming of the payouts from wrongful conviction filings in civil court.

Judge Shanes, presiding over the case due to conflict in Cook County, cleared Trutenko and Horvat of all 14 criminal counts against them in a legal saga that goes all the way back to the 1982 murders of two Chicago police officers. The charges levelled against Trutenko and Horvat in March 2023 included perjury, official misconduct, obstruction of justice, and the unprecedented charge of violating a local records act.

Trutenko, who served two stints in the State’s Attorney’s office for a total of 22 years, called the charges “novel and experimental,” and if successful would have not only opened all of his past cases to legal action, but the cases of all prosecutors in Cook County and nationwide.

Judge Daniel Shanes

| LinkedIn

“It’s like the saying ‘show me the man and I’ll show you the crime,” Trutenko told Chicago City Wire. “Then, once you take down the first prosecutor, you cut, copy and paste and the rest will follow.”

He added that Cook County would have potentially been on the hook for payouts in wrongful conviction settlements, payouts that have already cost the city of Chicago hundreds of millions in the past few years alone. Lawyers everywhere would take note, Trutenko said.

“Lawyers like to copy what other lawyers do especially if there is big money involved,” he said.

The criminal charges against Trutenko and Horvat stem from the prosecution of Jackie Wilson, who was convicted twice for his role, with his brother Andrew, of the 1982 murders of police officers William Fahey and Richard O’Brien on a South Side street.

Trutenko assisted in the prosecution of the second trial of Andew Wilson in 1988, and then with Bill Merritt, led the prosecution of Jackie in 1989. He won convictions in both cases.

Fast forward to 2018 when Cook County Judge William Hooks, a judge with an anti-cop reputation, ordered a third trial based on claims by Jackie that police tortured him into confessing to the murder.

It was then that Wilson was to become what former Chicago FOP spokesman and author of the column Crooked City, Martin Preib, called the “crown jewel” of the exoneration industry precisely because he was a convicted cop killer. Trutenko’s only crime, as it turned out, was standing in the way of the portrayal of Wilson as victim rather than perpetrator.

In October 2020, the third Jackie Wilson trial began and Trutenko was put on the stand. Horvat was assigned by the State’s Attorney’s office as Trutenko’s lawyer during the trial.

Trutenko was ambushed by Wilson attorney Elliot Slosar of the prominent Chicago plaintiff’s firm of Loevy & Loevy when he brought up a friendship Trutenko had with a prison informant, William Coleman, a British citizen, in the 1989 trial.

Slosar produced a baptismal certificate showing Trutenko as godfather to one of Coleman’s children. Slosar inferred that the friendship had already existed in 1989.

On the stand, Trutenko admitted the relationship but what was not revealed by Slosar or numerous media reports following the case was that the relationship had no bearing on the 1989 trial. It began years after the trial when Trutenko was in private practice.

“He began calling me when I was in private practice,” Trutenko said of Coleman. “He told me how he was turning his life around. Then one day he called saying that I was one of the only decent people he ever knew, and asked me to be godfather to his daughter. I was hesitant at first, but he kept persisting and I finally agreed.”

But Slosar’s gambit worked. The special prosecutors, Lawrence Rosen and Myles O’Rourke, assigned to the case—even though they had never before prosecuted a murder case—quickly dropped all charges against Wilson, and Trutenko was fired from the State’s Attorney’s office that very day.

In his acquittal order of Trutenko and Horvat, Judge Shanes called out Slosar, and Rosen and O’Rourke.

Shanes wrote that Slosar, “deliberately withheld evidence” from special prosecutors, while “prioritizing courtroom theatrics over his own legal obligations.”

“Before this court, Slosar professed an ignorance of his discovery obligations (which is disturbing enough),” Shanes wrote, “but his own notes preparing for an examination of Trutenko reflect his plan to play a game of ‘gotcha,’ deliberatively concealing the baptismal certificate until Trutenko testified, hoping for what Slosar himself described as a ‘set up.’ While trial by ambush makes for an entertaining Perry Mason scene, modern rules of evidence are designed to enhance the fairness of proceedings and avoid unnecessary litigation.”

Turning to Rosen and O’Rourke, Shanes quoted author G.K. Chesterton: “If a thing is worth doing, it’s worth doing badly.”

“That fairly sums up the 2020 proceedings,” Shanes said. “And because the 2020 proceedings form the basis for this case, the deficient performance of the attorneys there, disturbingly awash with inexperience and amateurism, provides a particularly challenging and fractured foundation here.”

The fight now for Trutenko, he says, is getting his good name back, a name tarnished by one-sided press coverage of the trial.

“I’m almost 70,” he said. “The only thing I can leave behind to my kids is the reputation and good name that took years to build.”

Alerts Sign-up

Alerts Sign-up