Recent changes in the way the Chicago Public Schools (CPS) is providing special education services and Individualized Education Programs (IEP) has ignited rage among parents, a questionable explanation from the CPS and a mathematical analysis by a watchdog group, the Better Government Association (BGA) reported recently.

The BGA says it reviewed statistics and disagrees with the CPS assertion that recent denials or delays in services are based on the fact that children of color are over-identified as special ed students.

The watchdog group said it determined that 23 percent of the students who have IEPs and are receiving specialized services are white, although only 10 percent of the student body is white. In contrast, African-American and Hispanic students comprise 38 percent and 46 percent of the entire student body, respectively, but make up 30 and 27 percent of students with IEPs.

Parents also say they are facing delays with children already diagnosed and receiving an IEP.

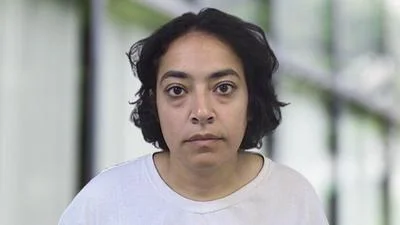

Lakeview resident Venessa Fawley's autistic daughter's IEP was revoked when she transitioned from preschool to kindergarten.

“It’s been an absolute nightmare,” Fawley told the BGA. “They literally make you question yourself as a parent and make you question what is wrong with your child.”

In addition to denying and delaying evaluations and services to disabled students, CPS dropped special transportation services at the beginning of the school year. Transportation for disabled students was reinstated after parents and activists complained.

CPS has also mixed special education funds with general education funds and added time to the lengthy IEP evaluation and issuance period.

Parents, teachers and activists took the issue to the Chicago Board of Education meeting last month and then protested outside of Mayor Rahm Emanuel's office at city hall. The Chicago Teachers Union has also taken up the issue, including the extra interventions that teachers are required to complete before children are granted evaluations by CPS.

The school is required to complete the evaluation within 60 days after the parent approves it, but teachers must collect data for 10 weeks first, which puts the children in limbo for months.

“I’m not trying to get something from the system that my kid doesn’t need,” Fawley told the BGA. “I want her to have everything she can so she can keep thriving, not to fail and then do it at all over again.”

Alerts Sign-up

Alerts Sign-up